Nota Bene: This post is littered with spoilers. Do NOT proceed if you wish to preserve the discussed text as terra incognita.

Have you ever thought of making history? Too much to ask? Alright, how about: have you ever thought of where you live as belonging to…the march of history? As being swept up and along by the tides of history? As 19th century Edo Japan was by invading Western powers, sustained contact with which making modernization a paramount exigency for the island nation, this anticipation of sweeping historical change being allegorized in the ukiyo-e painting The Great Wave off Kanagawa by Hokusai:

One day you’re rowing a skiff, hauling fish on board; the next day you’re a salaryman working overtime for Shimizu Corporation, drawing the blueprint for yet another high-rise office building.

How did things change so drastically, so fast, as history progressed?

But there are places history does not quite sweep along. Such places exist in the margins of history, it could be said. That a place could exist in the margins of history has always been true—even before the Great Divergence and the consequent colonial relationships imposed by Western nations upon their subjects in other parts of the world. Urban centers and palace courts have always been where history is made and written down—or written down and made, depending on how much of a narrativist you are. Agrestic settings, unless battlefields can be found, do not leave lines in the tomes of history.

None of the above should be mistaken for anything resembling a chauvinistic discourse with Hegelian echoes about stages of World History and, inversely, the impossibility of history in peripheral places. What I wish to underscore, instead, is how the passage of time as marked by significant events is interpreted by different groups of people not at all in one given way.

The Western literate worldview, with its emphasis on scientific and social progress, loaded as these terms are, is a very distinct and unusual one, when considered from the perspective of a community embedded in another cultural matrix: oral cultures, for a broad example. The Western conception of history is a literature-centric one. It is not the only conception of how the past can be recorded, though we who are steeped in Western texts and discourses are conditioned to label other conceptions of history as folklore, myth, or legend. In the Western worldview, a clear distinction has to be established between history proper and “history” recorded in less reliable ways, or the idea of historical progress risks losing its coherence.

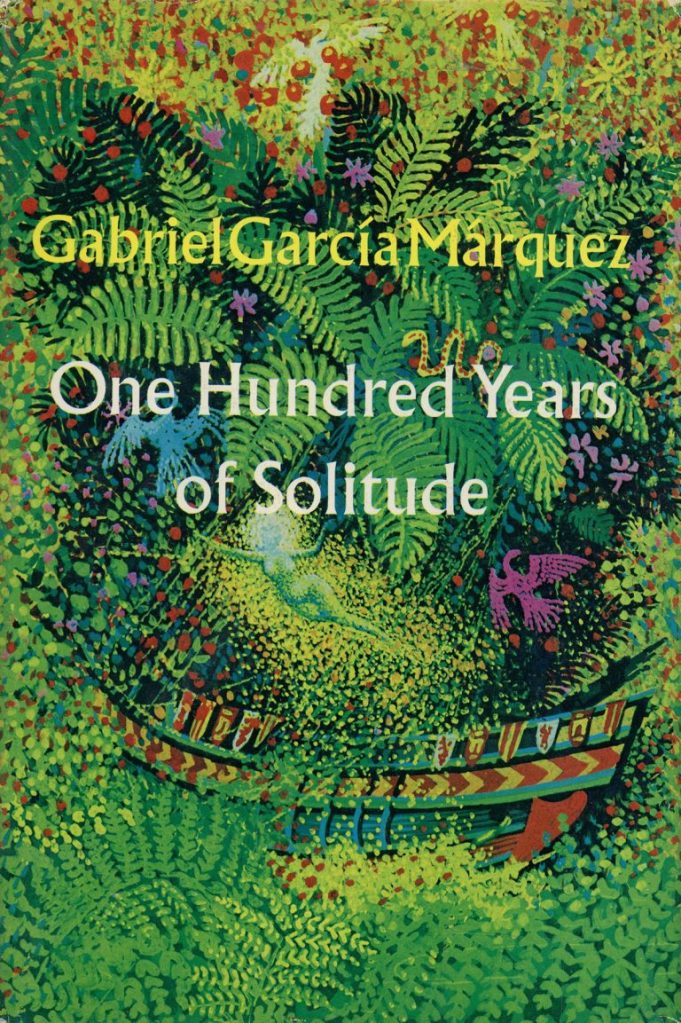

Macondo, the setting of One Hundred Years of Solitude, a work written by Gabriel Garcia Márquez and first published in 1967, is one such place where the march of history does not cross. Vaguely set in Colombia (where Márquez is from) around the cusp of the 19th and 20th century, Macondo exists in the swampy margins, but there are reverberations that the march of history creates in this village community. The margins of History are not, after all, the outside of History.

Macondo’s founding is, in a distant sense, connected to a Western (i.e. official) historical event. The village is founded by the couple Úrsula Iguarán and José Arcadio Buendía, and the narrative traces the lives of the many generations of descendants they have, many of these descendants bearing iterations of their progenitor’s names. Úrsula and José Arcadio Buendía left the town they were originally from to found Macondo because José Arcadio Buendía had killed a guy who insulted his virility, and the spirit of the slain man haunted the couple with his inextinguishable sorrow, the sorrow of having to leave his family behind. But even before that,

[w]hen the pirate Sir Francis Drake attacked Riohacha in the sixteenth century, Úrsula Iguarán’s great-great-grandmother became so frightened with the ringing of alarm bells and the firing of cannons that she lost control of her nerves and sat down on a lighted stove.

p. 21

This injury would set off a chain of events to bring the preceding generations of Úrsula and José Arcadio Buendía closer together, leading to inter-marriages, with the eventual result being that Úrsula and José Arcadio Buendía end up married to each other, though they are cousins.

Macondo was never intended to be a historically marginal place; it was intended to be situated right by the sea—to receive the tidings of historical progress—but its founders got lost.

From the cloudy summit they saw the immense aquatic expanse of the great swamp as it spread out toward the other side of the world. But they never found the sea. One night, after several months of lost wandering through the swamps, far away now from the last Indians they had met on their way, they camped on the banks of a stony river whose waters were like a torrent of frozen glass.

[…]

On the following day he convinced his men that they would never find the sea. He ordered them to cut down the trees to make a clearing beside the river, at the coolest spot on the bank, and there they founded the village.

pp. 26-27

Proximity to the sea would have provided Macondo surer access to news of global political events and knowledge of the latest inventions. Distance from which can be vexing, as it is to José Arcadio Buendía.

“We’ll never get anywhere,” he lamented to Úrsula. “We’re going to rot our lives away here without receiving the benefits of science.”

p. 13

Yet Macondo has its own channel of communication with the historically charged outside world: gypsies. The novel is a work of magical realism, which is to say that the narrative depicts human relationships and societies in realistic ways, but magical elements abound in the plot, so what we would separately call magic and modern technology are lumped together in the voice of narration. When gypsies display, as ware, wonders like a “flying carpet” (p. 37) or “false teeth” (p. 8), the inhabitants of Macondo uniformly see them as revealed mysteries of the world. José Arcadio Buendía does not recognize ice for what it is when he sees a block of it, mistaking it for diamond (p. 18). He also thinks ice contains an innate “deep meaning” to be understood.

He thought that in the near future they would be able to manufacture blocks of ice on a large scale from such a common material as water and with them build the new houses of the village.

p. 27

This commingled perspective on magic and modernity speaks to the novel’s position on Macondo’s historical marginality, which is itself a statement on how European colonization has inalterably changed the indigenous peoples of Colombia by erasing their traditional narrative modes and systems of knowledge.

There are strange disappearances throughout the novel, magical and sinister, that can be taken collectively as a master metaphor for European erasure of South American indigeneity.

First, the tribe of Melquíades, the gypsy who introduces ice and many other inventions and discoveries to Macondo, disappears.

[…] Melquíades’ tribe, according to what the wanderers said, had been wiped off the face of the earth because they had gone beyond the limits of human knowledge.

p. 42

Human or European knowledge?

Then, it’s a large-scale human atrocity committed by an American banana company against striking workers that gets entirely erased from historical records.

Every time that Aureliano mentioned the matter, not only the proprietress but some people older than she would repudiate the myth of the workers hemmed in at the station and the train with two hundred cars loaded with dead people, and they would even insist that, after all, everything had been set forth in judicial documents and in primary-school textbooks: that the banana company had never existed. So that Aureliano and Gabriel were linked by a kind of complicity based on real facts that no one believed in, and which had affected their lives to the point that both of them found themselves off course in the tide of a world that had ended and of which only the nostalgia remained.

p. 419

Eventually, it’s Macondo itself that has to disappear without a trace. The disappearance is both gradual and sudden. Gradual, because the village had begun depopulating and falling into disrepair over the course of one hundred years of historical progress happening around it. Modernizing influences are everywhere: a civil war for independence of conservatives against liberals in the style of Western politics, the American banana company and the city it set up to house workers, a connecting railroad, the importation of European luxury commodities such as clavichords, classical learning, and so forth. All these would strip Macondo not just of its inhabitants but its spirit.

One winter night while the soup was boiling in the fireplace, [the Catalonian who moved to Macondo to set up a bookstore selling European books] missed the heat of the back of his store, the buzzing of the sun on the dusty almond trees, the whistle of the train during the lethargy of siesta time, just as in Macondo he had missed the winter soup in the fireplace, the cries of the coffee vendor, and the fleeting larks of springtime. Upset by two nostalgias facing each other like two mirrors, he lost his marvelous sense of unreality and he ended up recommending to all of them that they leave Macondo, that they forget everything he had taught them about the world and the human heart, that they shit on Horace, and that wherever they might be they always remember that the past was a lie, that memory has no return, that every spring gone by could never be recovered, and that the wildest and most tenacious love was an ephemeral truth in the end. Álvaro was the first to take the advice to abandon Macondo. He sold everything, even the tame jaguar that teased passersby from the courtyard of his house, and he bought an eternal ticket on a train that never stopped traveling. In the postcards that he sent from the way stations he would describe with shouts the instantaneous images that he had seen from the window of his coach, and it was as if he were tearing up and throwing into oblivion some long, evanescent poem: the chimerical Negroes in the cotton fields of Louisiana, the winged horses in the bluegrass of Kentucky, the Greek lovers in the infernal sunsets of Arizona, the girl in the red sweater painting watercolors by a lake in Michigan who waved at him with her brushes, not to say farewell but out of hope, because she did not know that she was watching a train with no return passing by. Then Alfonso and Germán left one Saturday with the idea of coming back on Monday, but nothing more was ever heard of them. A year after the departure of the wise Catalonian the only one left in Macondo was Gabriel, still adrift at the mercy of Nigromanta’s chancy charity and answering the questions of a contest in a French magazine in which the first prize was a trip to Paris. Aureliano, who was the one who subscribed to it, helped him fill in the answers, sometimes in his house but most of the time among the ceramic bottles and atmosphere of valerian in the only pharmacy left in Macondo, where Mercedes, Gabriel’s stealthy girlfriend, lived. It was the last that remained of a past whose annihilation had not taken place because it was still in a process of annihilation, consuming itself from within, ending at every moment but never ending its ending. The town had reached such extremes of inactivity that when Gabriel won the contest and left for Paris with two changes of clothing, a pair of shoes, and the complete works of Rabelais, he had to signal the engineer to stop the train and pick him up. The old Street of the Turks was at that time an abandoned corner where the last Arabs were letting themselves be dragged off to death with the age-old custom of sitting in their doorways, although it had been many years since they had sold the last yard of diagonal cloth, and in the shadowy showcases only the decapitated manikins remained. The banana company’s city, which Patricia Brown may have tried to evoke for her grandchildren during the nights of intolerance and dill pickles in Prattville, Alabama, was a plain of wild grass. The ancient priest who had taken Father Ángel’s place and whose name no one had bothered to find out awaited God’s mercy stretched out casually in a hammock, tortured by arthritis and the insomnia of doubt while the lizards and rats fought over the inheritance of the nearby church. In that Macondo forgotten even by the birds, where the dust and the heat had become so strong that it was difficult to breathe, secluded by solitude and love and by the solitude of love in a house where it was almost impossible to sleep because of the noise of the red ants, Aureliano and Amaranta Úrsula were the only happy beings, and the most happy on the face of the earth.

pp. 432-434

Macondo has been modernized to the point of losing its fundamental character, and with that, its inhabitants, who make the choice to leave for the wider modern world. But the last two of the founding lineage remain. As with the first couple, so with the last: incest once again, and a great torrential love affair it is that Aureliano and Amaranta Úrsula get themselves into, Úrsula writing a letter to end things with her husband, the couple eventually producing a child from their ceaseless love-making.

It is after the birth of the child that time begins to run out for the founding lineage and, also, the setting of Macondo itself. The wife dies from excessive bleeding during childbirth. The grieving husband Aureliano neglects the child, who is born with a pig’s tail, the realization of a generational fear of incest, and the child is eaten by ants; Aureliano remembers that Melquíades, a student of Nostradamus, had predicted the child’s death by ants in a book he wrote. He opens the prophetic book to find that it contains everything that has happened in the past 100 years concerning Macondo. Yet, as he’s reading, violent swirling currents of wind are tearing apart and removing the infrastructure of Macondo.

Macondo was already a fearful whirlwind of dust and rubble being spun about by the wrath of the biblical hurricane when Aureliano skipped eleven pages so as not to lose time with facts he knew only too well, and he began to decipher the instant that he was living, deciphering it as he lived it, prophesying himself in the act of deciphering the last page of the parchments, as if he were looking into a speaking mirror. Then he skipped again to anticipate the predictions and ascertain the date and circumstances of his death.

Before reaching the final line, however, he had already understood that he would never leave that room, for it was foreseen that the city of mirrors (or mirages) would be wiped out by the wind and exiled from the memory of men at the precise moment when Aureliano Babilonia would finish deciphering the parchments, and that everything written on them was unrepeatable since time immemorial and forever more, because races condemned to one hundred years of solitude did not have a second opportunity on earth.

pp. 447-448

The race that inhabits Macondo are a race of people who live in History’s margins; they were condemned to be eliminated the moment History made its incursions upon them. Aureliano, reading Melquíades’ book, realizes everything that had happened was predestined the moment Sir Francis Drake attacked Riohacha.

Only then did he discover that […] Sir Francis Drake had attacked Riohacha only so that [Aureliano and Amaranta Úrsula] could seek each other through the most intricate labyrinths of blood until they would engender the mythological animal that was to bring the line to an end.

p. 447

The mythological animal mentioned is Aureliano’s son, born with an incest-engendered pig’s tail. The recurring theme of incest in this novel is not to be taken as something included merely to scandalize the reader. Bear in mind that Melquíades prophetic book is “a history of the family” (p. 446). It is, as the novel itself is, a record of passions, love affairs, affiliation, lineage, fanciful adventures, and magical incidents. It is a traditional mode of reckoning with the past that the official narrative of (Western) History prohibits, a form of story-telling that has to be forced into the margins and then finally erased.

Melquíades’ tribe, the victims of the banana company massacre, Macondo: anyone who has no place in the Western worldview of historical progress, scientific or social, has to be denied remembrance. The margins of history present a threat to official historiography and have to be dealt with accordingly.

Solitude isn’t isolation; the one hundred years of solitude in this novel aren’t a hundred years of being left alone; it is a hundred years of alienation and dread, a hundred years of the community of Macondo sensing their eventual erasure as more and more of who and what they are get dismantled by the reverberations caused by the march of History. History’s margins, as Márquez sees it, meet with only one type of end: eradication.

One Hundred Years of Solitude is a novel to make the reader realize the power of storytelling is a notion that contains grave and sinister overtones. As much as stories empower the marginalized by giving them a voice, just as much is entrenched power able to control which stories count and which don’t. What matters is not just whose story we tell, but how we tell them, if we wish not to erase the existence of those who live in History’s margins.

Works Cited

Márquez, Gabriel Garcia. One Hundred Years of Solitude. Trans. Gregory Rabassa. Ashland, Oregon: Blackstone Publishing, 2022. Kindle Digital.

Leave a comment